There are books about Scottish art and Scottish artists, and they read like a pantheon of ‘greats’. The authors choose well-known stars like Alan Ramsay, David Wilkie, William McTaggart, Charles Rennie MacIntosh, The Scottish Colourists, The Glasgow boys, Susan Phillipsz. Even Joan Eardley will get a shoe-in, despite being born in Sussex. Celebrity status is important in selling exhibition tickets and books.

It’s a problem though to choose examples of Scottish art because there’s no agreement on what ‘Scottish’ means. Are these artists just good examples of quality, or do they create something exquisitely different that cannot be found anywhere else? Is ‘Scottishness’ an essential characteristic to be measured against ‘Italianness’, ‘Somalianness’ or ‘Englishness’? How Scottish am I compared to you? Are the Scottish Tories distinctively different from other Tories?

Questions like these underline the flexibility of the term. When Scottish means an ethnic group, then that identity can only be loosely defined and will be consistently contested. It cannot be a reasonable benchmark to evaluate anything, including art, against.

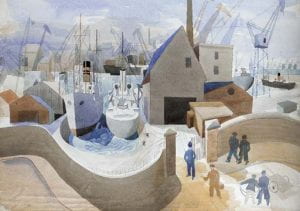

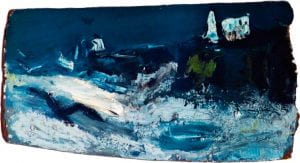

Yet, there is one aspect of ‘Scottishness’ that is distinct, that is different from any other ‘ishness’ on the planet….the place, the territory that we currently call ‘Scotland’. This place provides the context that any artist who works here shares, even if they live in different centuries.

The definitive criterion of Scottishness is the presence and influence of Scotland itself – the land, its spaces, places, locations and peoples. This influences what anybody does here in this place, irrespective of where they were born or who their parents were.