Paintings of the sea almost always show the ocean as a 2D surface. Whilst we know that there is a depth of material, of colour, of light and shadow, beneath the constantly moving water, we can neither see nor hear it. Yet there are paintings of the Scottish sea beneath the waves.

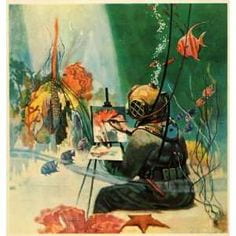

Zarh Pritchard (1866-1956), regularly bathed in the Firth of Forth from Portobello beach from the age of 10 and in his teens, he began to sketch what he had seen when swimming below the waves. Following an education in Art in Edinburgh, he learned in Tahiti how to paint below the surface. His were the first underwater paintings, proper seascapes.

His biographer, Elizabeth N. Shor writes that ‘for his underwater work Pritchard used lambskin soaked with oil and brushes thoroughly soaked in oil. Wearing a diver’s helmet, serviced by a tank from a boat on the surface, he sank to the seafloor with a coral or stone weight, selected the view that he wanted, had his canvas and materials lowered to him from the boat above, and painted for about half an hour’.

He painted, fully immersed, off Tahiti and Scotland and other shores.

His paintings give us a different view of the Scottish seas, a space