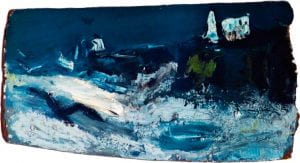

Imagine, if you will, what kind of day Joan Eardley had as she stood on the foreshore painting this picture of the sea-foam at Catterline, a coastal village on the North Sea in Scotland.

An artist’s sensory experiences (of the sound of the water, the touch of the wind, the smell of seaweed and brine, the grind of sand on the skin) must surely, like everyone else’s sensory experiences, be incorporated into what they feel and do, into their way of being in the world. The resultant painting then comes full circle, because it in turn influences everyone who looks at the picture. Each viewer thinks about this portrait of the sea, incorporates something of what the artist has left there and carries around a new perspective, even when they themselves go to the sea in the future.

It is no surprise that many visit Catterline to ‘see’ what Eardley saw, to compare the painted place with the ‘real’ place. This small thought experiment begs the question: how do people experience the Scottish sea and what has it added to their sense of self?